n our recent energy analysis for this project, we uncovered three particularly interesting cases that we’ll explore in this post.

Insulating isn’t always as simple as ‘throwing a blanket over it.’ At times, building physics plays curious tricks on us, where geometry and materials defy common logic. Most software—ranging from simplified calculation methods based on UNE-EN ISO 52016-1 (such as CE3X or CERMA) to more advanced dynamic simulation tools like EnergyPlus—simplifies models by reducing the building envelope to one-dimensional components. While this allows for fast and accurate calculations, we lose relevant data regarding actual heat flow.

Therefore, the inclusion of thermal bridges should be understood more as a ‘fine-tuning’ of the thermal model—to account for specific geometric and constructive details—rather than an absolute reality. A thermal bridge in one constructive solution cannot be compared to another in isolation; it depends entirely on its context.

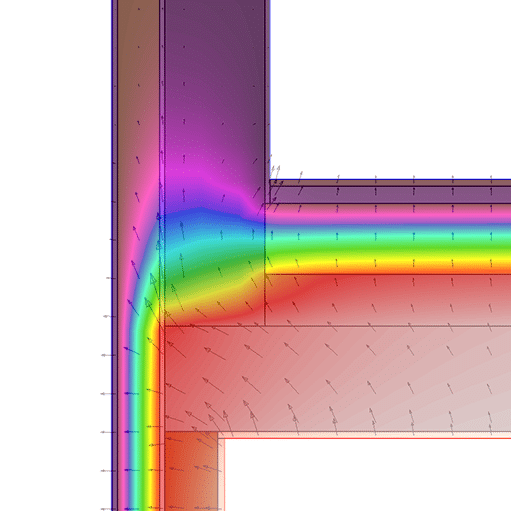

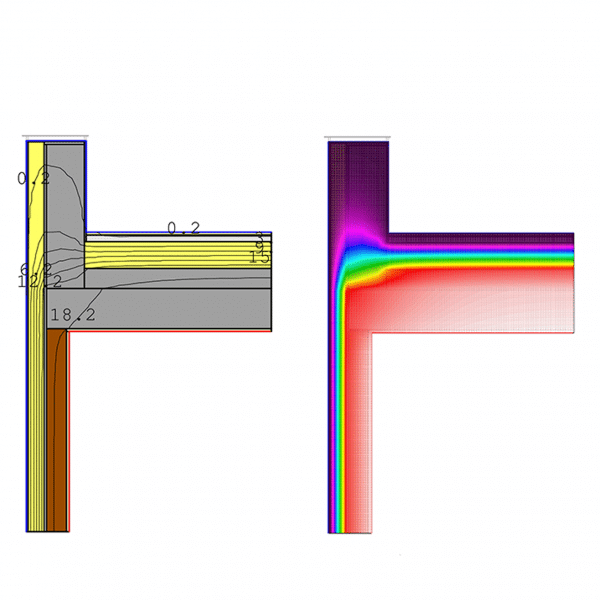

1. The “Funnel Effect” at the Window Opening

- The Paradox: We insulate the facade from the exterior (ETICS/EIFS) and even wrap the insulation around the window frame, yet the thermal bridge value psi increases.

- Why does this happen? When we apply “super-insulation” to the facade and switch to high-performance windows, the overall thermal resistance of the assembly increases drastically. If the insulation return at the reveal isn’t equally robust, or if the window isn’t perfectly aligned with the insulation layer, heat “concentrates” there.

- The Modeling Nuance: Strictly speaking, it’s not that heat “seeks” an exit; rather, compared to the vastly improved facade, that specific point is now significantly weaker. Since the one-dimensional model hadn’t accounted for this disparity, the psi coefficient rises to compensate for it.

- The Irony: If we were to leave the facade uninsulated (with poor transmittance), the thermal bridge at that same window reveal would actually appear “better” in the calculations. This proves that $\psi$ is not an absolute value, but a relative one—it depends entirely on its surroundings.

- Conclusion: The positioning of the window frame relative to the insulation layer is critical to prevent heat flow concentration.

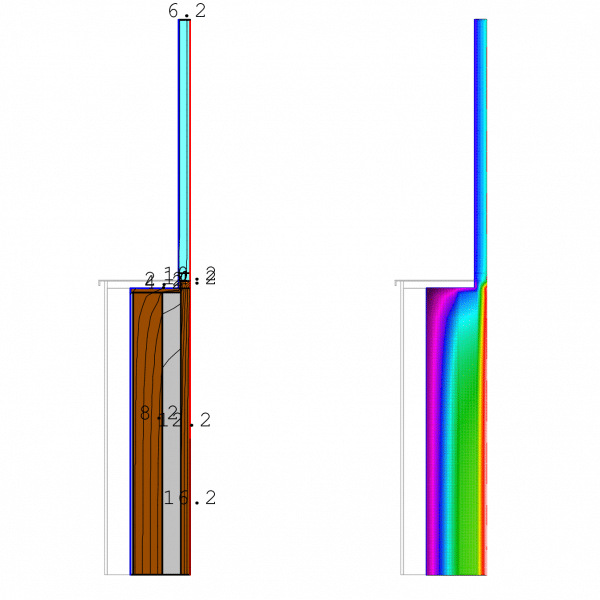

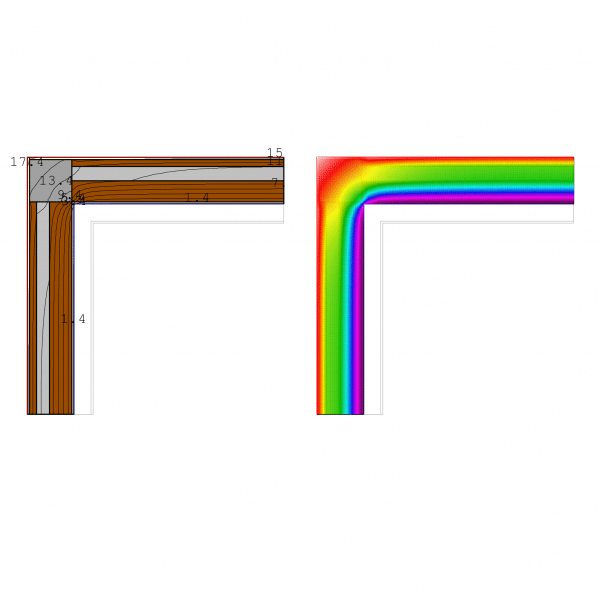

Case 1.1: The Baseline – Pre-Renovation

Initial state: Before window replacement and ETICS installation. Thermal Bridge Value psi: 0.11 W/mK

Case 1.2: The “Improvement” – High-Performance Upgrade

Updated state: We install 12 cm of ETICS (SATE) and replace the windows with high-performance units (Uw value below 1.40 W/m²K—super-insulating!). The window perimeter (jambs and sill) is protected with a 4 cm EPS insulation return. Thermal Bridge Value psi: 0.13 W/mK

Case 1.3: The Optimized Solution – Maximum Insulation Return

Updated state: This scenario improves upon Case 1.2 by increasing the EPS insulation return to 8 cm on both the sill and the jambs. Thermal Bridge Value psi: 0.03 W/mK

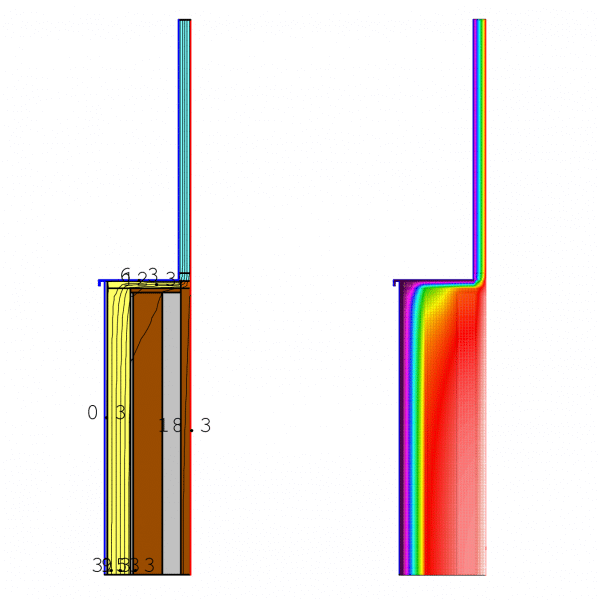

2. The Mysterious “Negative Thermal Bridge”

- The Paradox: In internal corners (incoming corners, where the exterior forms a “concave” shape), the psi coefficient is often negative. Does this mean the corner is somehow generating heat? We wish!

- Why does it happen? It is a matter of pure geometry and how we measure. Normally, in energy certification calculations (such as CE3X or other European standards), we use exterior dimensions.

- The Explanation: In a concave or internal corner, the exterior surface area is much smaller than the interior surface area. When we calculate total heat loss using the exterior area as a base, the standard formulas overestimate how much energy is actually escaping.

- The Adjustment: To correct this overcalculation and ensure the energy balance matches reality, the psi value must be negative. It acts as a mathematical correction factor, ensuring we don’t unfairly penalize the wall’s efficiency.

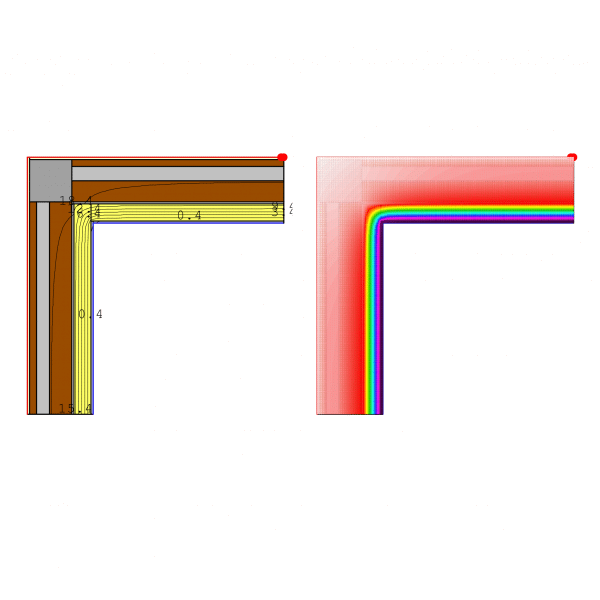

Case 2.1: The Baseline – The Corner Column

Initial state: No ETICS (SATE) protection on the well-known “corner column” thermal bridge. Thermal Bridge Value psi: -0.55 W/mK

Case 2.2: Insulating the Corner

Updated state: The facade is now insulated with an ETICS (SATE) system. Thermal Bridge Value psi: -0.17 W/mK

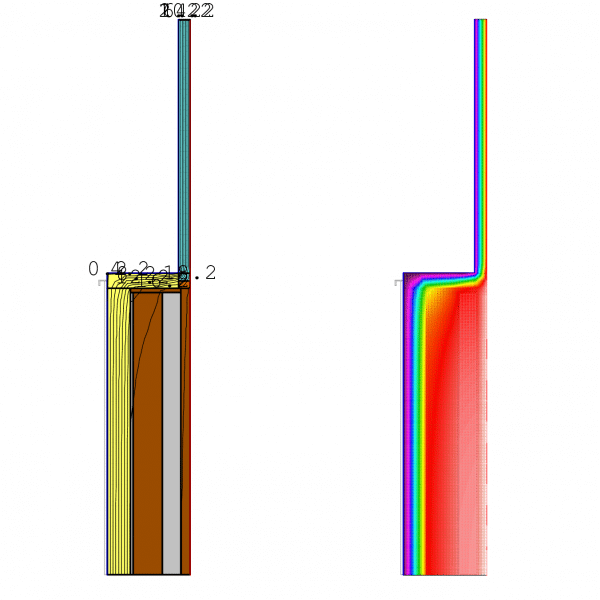

3. La paradoja del antepecho: Geometría vs. Resistencia

-

La paradoja: Un antepecho de hormigón celular sin una sola placa de aislante puede ser térmicamente más eficiente que un antepecho de hormigón armado envuelto en 10 cm de aislamiento.

- El concepto clave: El “atajo” del calor. En un antepecho convencional de bloque o hormigón armado, para evitar el puente térmico, nos vemos obligados a “envolver” todo el murete. Esto genera una superficie de intercambio enorme: el calor tiene una “autopista” por el hormigón y una gran superficie de salida a través del aislante.

- La ventaja del hormigón celular: Al sustituir el bloque por hormigón celular (que tiene una conductividad mucho menor que el armado, aunque peor que un aislante puro), eliminamos la necesidad de envolverlo.

- El balance final: El flujo de calor se limita estrictamente a la sección del muro. Aunque el material resiste menos que la lana de roca o el EPS, la superficie y longitud de exposición son tan pequeñas comparadas con la “envolvente completa” del caso tradicional, que las pérdidas totales son menores.

- Menos es más: Una superficie de pérdida reducida compensa con creces una conductividad ligeramente superior.

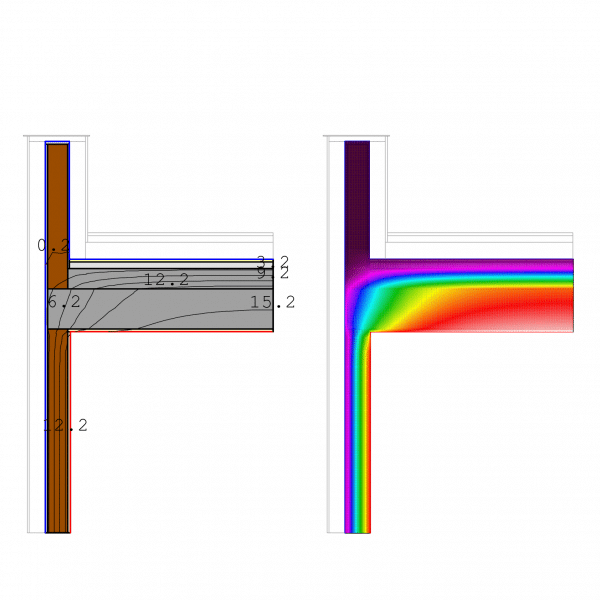

Caso 3.1. Es el estado inicial con el antepecho de ladrillo perforado Sin la protección de SATE ni el aislamiento en la cubierta. La ψ: Transmitancia Puente térmico = 0,73W/mK

Caso 3.2. Aislamos con 12 cm de EPS en fachada i el antepecho con 4 cm, la cubierta aislada con XPS 20 cm. Obtenemos una ψ: Transmitancia Puente térmico =0,22 W/mK

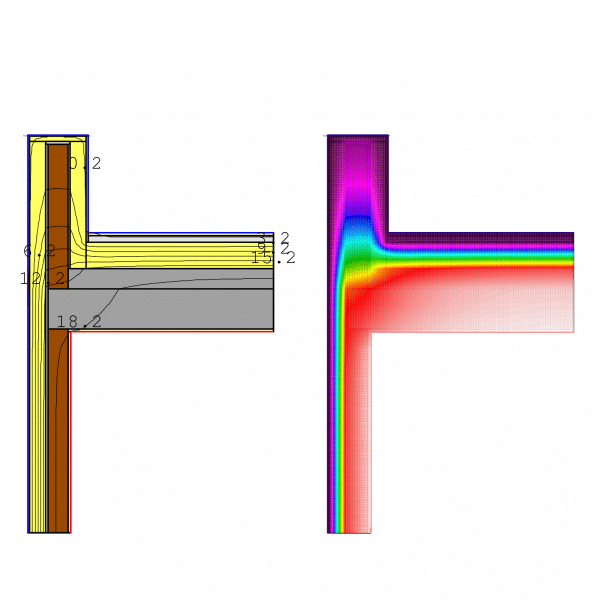

Case 3.3: The Pragmatic Alternative – Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (AAC)

Updated state: We decide against insulating the parapet itself. Instead, we propose using a 25 cm wide autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) block with a thermal conductivity of PSI= 0.09 W/mK, while the roof remains insulated with 20 cm of XPS. This approach is significantly simpler to build than the previous case. Thermal Bridge Value psi: 0.15 W/mK

Conclusions

Thermal bridges are not merely ‘cold spots’; they are energy flow nodes that expose the precision limits of our models. Understanding that geometry (Case 2) and the intrinsic resistance of materials (Case 3) take precedence over the sheer quantity of insulation (Case 1) is what distinguishes an energy efficiency expert from a simple insulation salesperson.

Thermal bridging can influence energy demand by 20% to 40%; for this reason, it is vital to account for them from the very beginning of the design phase. In building retrofits, the constructive detail is not an afterthought—it is the key to success.